Heat pumps are not a new concept. First developed at the start of the 20th Century, they operate successfully in a diverse range of applications. Many of us have at least one in our homes in the form of a domestic refrigerator. Air conditioning units providing comfort cooling are also heat pumps.

Heat pumps give thermodynamic heating (or cooling) by means of a vapour compression cycle, in this case collecting heat from the air. First, it is important to understand a little more about the heat within air. Simply speaking, heat can be considered as a generic description of certain energy within a substance. Air contains two forms of heat that a heat pump can extract and convert into useful energy.

The most obvious form of heat in the air is ‘sensible’ energy, in other words, temperature. This energy accounts for something in the order of 70% of the heat pump’s energy source. The remaining 30% of heat that can be usefully extracted from air is the latent energy.

Latent energy is present within air as invisible moisture vapour, commonly expressed as humidity. By changing the state of this invisible moisture back to water (and even ice when the air is cold enough) the heat pump can convert the latent energy, which was required to evaporate the water in the first place, into useful sensible heat. From this you will realise that heat pumps do not rely upon the air temperature alone, rather the total usable energy content of the air.

Matter contains energy down to the temperature called ‘absolute zero’, the minimum theoretical temperature, or -273.15°C in more familiar units. Heat pumps are capable of practically extracting this energy in air temperatures as low as -15°C.

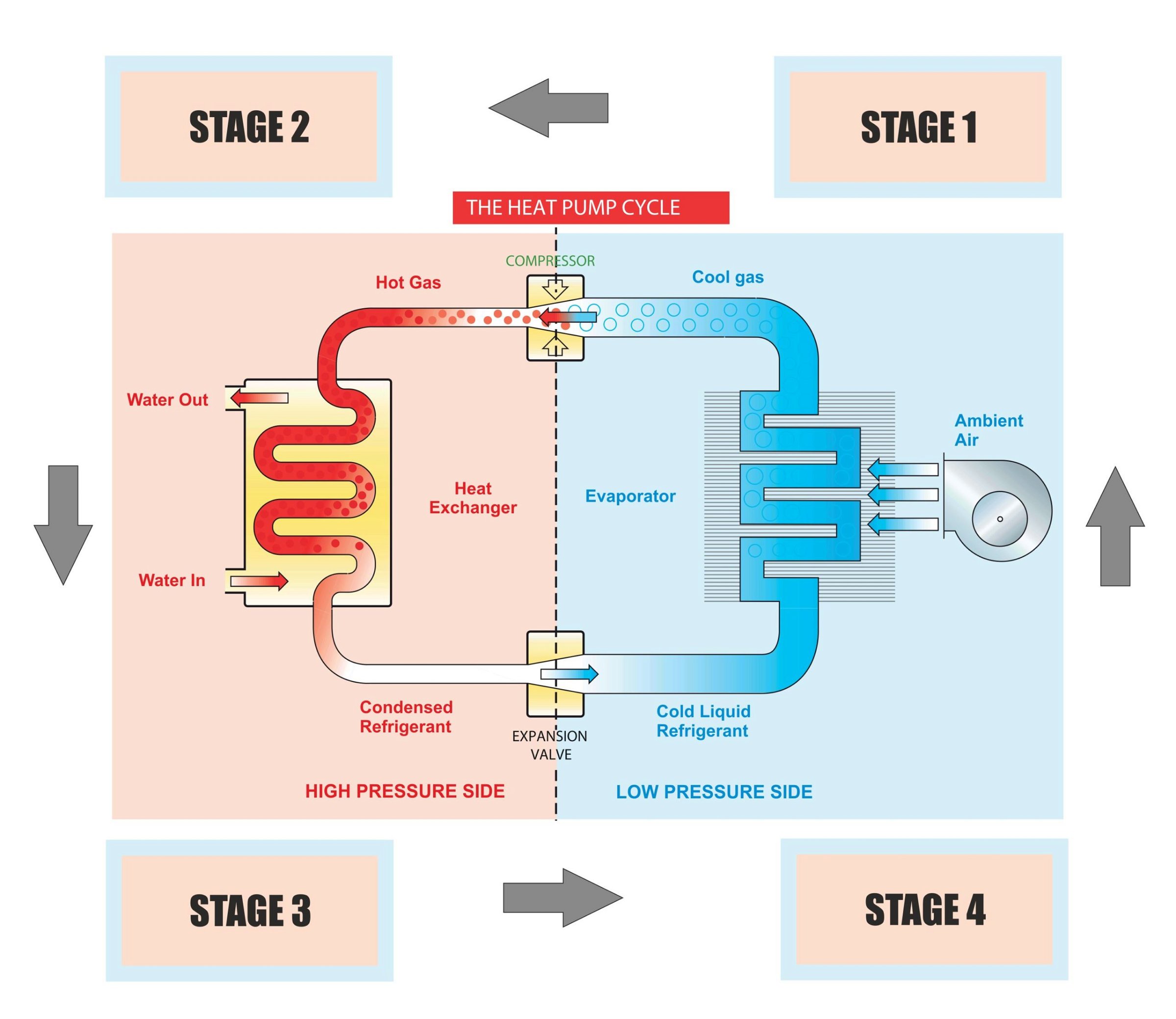

Next we will consider the basic components that make such a system work (the illustration below shows the main components):